3. Making assertions with Chai

Why Chai?

As mentioned in the structure, a test case goes red when anything in the it block throws an exception. First of all, by calling a function in specs we expect that it has been executed without any error. If the code seems to be pretty simple and writing specs for it sounds like a waste of time, it’s still worth to have them, at least for this information.

We can do better and actually expect specific behavior from the code. To do so in Mocha, we will need a function that throws an exception in the case of unmet requirements. Do you really need an assertion library to do that? Let’s take a look at this example:

function assert (condition, message) {

if (!condition) {

throw new Error(message)

}

}

assert(1 == 1, ‘1 is equal to 1’)

assert(isEven(2), ‘2 is an even number’)It’s dead simple, but it works. However, writing all error messages by hand is boring and it’s easy to leave them outdated.

A little bit more complex than that is the assert package - NodeJS built-in assertion library, with many web browsers compatible ports. It extends the interface of the assert function by a few additional methods, like assert.equal(value, otherValue, [message]).

Still, there is a problem with error messages. If you like the simplicity of the assert and want more descriptive error message out of the box, take a look at powerassert. It has the same API as assert, but automatically creates messages that are much more informative.

Since I see benefits of having both: descriptive error messages AND the test code itself, my library of choice is chai and its expect style. This way, you can chain keywords composing the expectation in a form as close as possible to grammatically correct sentences.

Instead of:

assert(value() === 1)

assert(otherValue().name === 'John')We can write:

expect(value()).to.equal(1)

expect(otherValue()).to.have.property('name').equal('John')The idea is that you can pass your subject to the expect() function and then chain all the checks you want to perform against the subject.

Be like -v

Even if you can reduce every case to an equality assertion, in BDD we are encouraged to be as verbose as possible in expectations. In practice, it means checking if there is any dedicated matcher for our case that we can use. We can also create our own matchers if needed.

For example, if you want to verify the property value, you can use:

expect(user.name).to.equal('James')but you can find the have.property() matcher more suitable for this case and write:

expect(user).to.have.property('name').equal('James')By using the whole object as the subject you will pass more context to the matcher and thanks to that the error message will be more descriptive. Also, the spec code will be easier to understand just by reading it. Combined with good block descriptions, you can make your specs code as readable as an essay.

Surprisingly, as a new guy in a big team working on a Ruby on Rails based application, without any previous experience with Ruby language, I was able to read and understand RSpec tests I’ve stumbled upon there. First of all, built-in verbose matchers were commonly used. Another thing was a whole bunch of custom matchers. I didn’t need to dig into the code, even didn’t need to know the programming language, to understand what is checked by:

it { is_expected.to increase_number_of_tasks_by(1) }Custom matchers allow hiding complexity of the code behind a readable curtain. In Chai, to add a custom matcher, you need to use the plugins API. Take a look and also read the Building a Helper tutorial, then try to implement a custom matcher in the example below.

{% tommy_example assertions-custom-matcher %}

Plugins

With a pluggable architecture like that, it’s possible to extract and share your custom matchers with others or patch existing matchers to work with some uncommon data. That’s what people do, for example, to integrate with other libraries or frameworks. You can count on chai-jquery when you want to make assertions on the DOM. Some of the plugins help simplify specs code, for example by wrapping Promise-based assertions in chai-as-promised. Check out the official list of plugins list of Chai plugins or get some hints from them and write your own.

Make sure it’s red

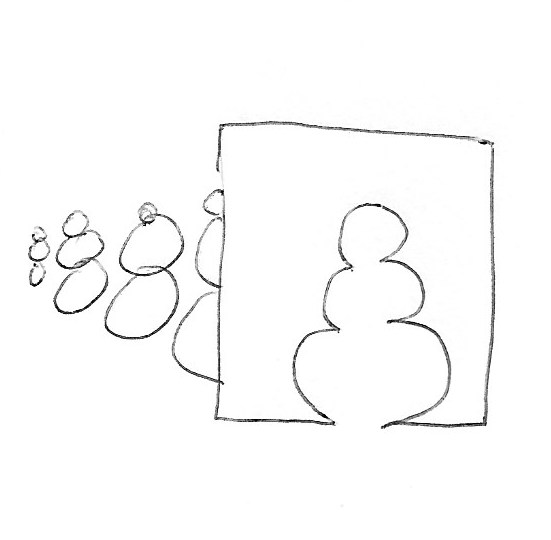

A child in the shop line, loud and red in the face, screaming until they get a snack. That’s what your assertion should be, unless the code works fine. Unfortunately, it’s quite possible that the spec added after implementation is rather the shop owner who puts on display the most delicious snacks, expecting people to desire them.

The point is, having a green spec is not enough to say it’s all good. It may be the case that it’s always green and it doesn’t give any feedback at all. A good practice is to try to break the spec, by changing the expectation or implementation for a moment. Seeing that broken code will cause a failure in the test suite is a very important part of the whole process. Thanks to that we know that the spec actually checks something and it will warn us if we accidentally break the behavior of the code during future modifications.

As a final excercise on this topic, please try to figure out what is wrong with the code below:

{% tommy_example assertions-false-negatives %}